By: Michael Tylka

Tampa Streetcars (http://www.railwaypreservation.com/vintagetrolley/Tampa_advertising_cars.JPG)

Many cities in the United States are reintroducing the streetcar as a tool to aid in the revitalization of urban cores. Questions can be asked in regards to their usefulness in a comprehensive transportation network, the level of benefit to economic development they provide, and their use in transit oriented development with the goal of increasing density. Streetcars are different than light rail as they coexist with traffic on city streets. Historically most cities in the nation had significant networks until automobile use skyrocketed and the creation of the interstate highway system. Attention to streetcars as part of a conversation on transportation and land use is warranted as city’s view them as a way to use transit to alter land uses and the urban form.

Those that sell the idea of modern streetcars mention benefits in terms of job growth, neighborhood reinvestment, environmental impact, connectivity/mobility, property values, and usefulness in combating congestion and raising travel costs. It has been stated by proponents of projects that the permanent nature of lines will lead to development and thus the above mentioned benefits. The argument here is that developers only feel comfortable making large investments along infrastructure networks that they feel are not going to go away. Bus rapid transit lines are significantly cheaper and I do not see why people would not view these as just as permanent. Part of me thinks that people simply like the appeal of streetcars as testament to days gone by and their historic nature, and not to forget the average American’s dislike of buses.

Robert Cerervo, a renowned transportation expert, has stated that streetcar usage is a vital part of a larger transportation network as streetcars can be used as circulator routes. In this the lines exist in the dense urban cores and people would most likely have to take another form of transit to get to the line if they did not live along the route or in the core. This is the type of network Cincinnati, Ohio is looking to build. I do question the idea that people are willing to take multiple forms of transportation in a mid-size city where one can easily find a place to park. If the line is not the most convenient option than why would the masses take them? Perhaps if the line does lead to further densification, the highest and best usage of land will not be for parking, and then we can look to see it being easier for a person to use the street car as a circulator. Toronto, Ontario is an example of a city that uses its streetcar network in conjunction with its light rail network and bus system. It makes virtually any area of the city quite accessible as the connectivity is expansive, but like earlier stated, this is a large city where parking and driving is inconvenient.

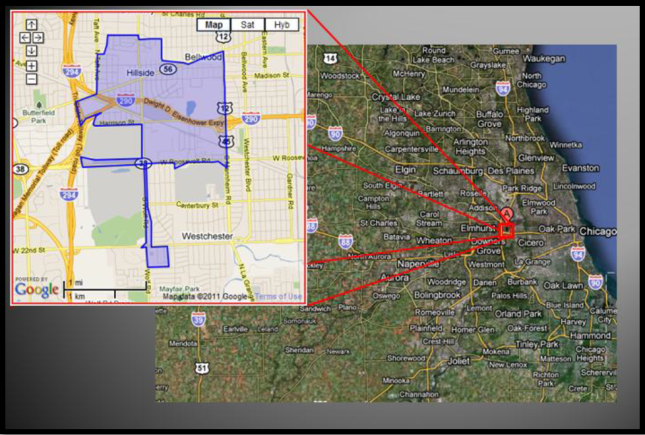

Map of Cincinnati Line Currently Under Construction – This displays that the line runs only in the urban core with plans to eventually connect to a college neighborhood – http://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/streetcar/design-route/

Economic development provided by an expanded transportation system is key to arguments for new systems. Critics of projects look to expose costs and other funding mechanisms used. Randal O’Toole in a report prepared for the John K. MacIver Institute for Public Policy points to tax breaks, subsidizes, and city investment along routes as the real reason behind development for the Portland, Oregon line. O’Toole is clear in stating that he feels streetcars are “long-obsolete technology”.(1) Also in Portland, O’Toole points to the use of TIF, tax increment financing, for projects and how this particular project only used $21 million of the $725 million of bonds for streetcar construction.(2) The money here was spent to improve other aspects of the districts and in stating this O’Toole is pointing to the fact that perhaps projects are being approved when the public is not fully informed who is benefiting from funding dollars. He feels that people like roads and cars therefore that is where money should be spent. In this he is only taking the initial construction costs, and not all the other benefits of mass transportation.

The City of Tucson, Arizona has a streetcar network that is often presented as a model for other cities. Their line runs between downtown and a major university campus. The Downtown Tucson Partnership claims that around 150 businesses have opened along the route and that approximately 2,000 jobs have been created.(3) One must ask if the line is the main reason for the revitalization and not other factors at play. Certain places such as this have large bodies of young people that are willing to ride between two particular locations. Cities must be careful in placing lines as not all cities will have populations such as this that are open to riding this form of mass transit and ones that are so concentrated.

Luckily for streetcar enthusiasts, the Obama administration in 2010 offered $130 million in federal funds for street car projects.(4) Detractors state that yes the lines may create jobs, but that the major concern is that the lines will require financial assistance for their entire lifetime.(5) The overwhelming majority of all forms of public transit are supported by governmental or private investment. The basic question here should be does that assistance create a positive return that is multiplied to the community. This should be answered by city officials before any streetcar lines are considered to be a viable option.

Streetcars should be considered as an option as part of a larger transportation network if their benefits are able to quantified. Yes it is difficult to know exactly the extent of their reach, but I would caution any city before near permanent expensive infrastructure is put in place. If lines truly are shown to bring people into urban cores than yes they could help in densification and in turn the repopulation of downtowns and blighted areas.

Works Cited:

[1] Randal O’Toole. The Streetcar Scam. MI Reports, prepared for The John K. MacIver Institute for Public Policy. http://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/articles/streetcarscam-otoole.pdf

[2] Randal O’Toole. The Streetcar Scam. MI Reports, prepared for The John K. MacIver Institute for Public Policy. http://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/articles/streetcarscam-otoole.pdf

[3] Daniel C. Vock. Cities turn to streetcars to spur economic development. November 8, 2013. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/11/08/stateline-streetcars/3475007/

[4] Katherine Dorsett. Can streetcars save America’s cities? December 17, 2010. http://www.cnn.com/2010/US/12/17/light.rail.streetcar/

[5] Katherine Dorsett. Can streetcars save America’s cities? December 17, 2010. http://www.cnn.com/2010/US/12/17/light.rail.streetcar/